Why does this newsletter exist? The simple answer is that I love history. It is entirely free, and you can unsubscribe at any time. If you received this email, it means you signed up for the Res Obscura newsletter at some point. And it could actually be a useful tool for making arguments about the validity of possible self-portraits, like the ones that da Vinci scholars have long argued over. I suspect that this would end up with something reasonably close to the artist’s own face. Theoretically, it should be possible to create a corpus of all non-portrait faces in a given artists’ known oeuvre, use AI tools to rotate them and even adjust the expression to make them comparable, then create a facial composite. But what about the painters who didn’t leave behind a known self-portrait? The examples of auto mimesis I gave above are all discoverable because we happen to have self-portraits of the artists. In other words, it’s now possible to rotate faces from artworks in new ways - even to animate them. This got me thinking about the recently-acquired ability of generative AI models to create 3D representations of 2D images. While researching this topic, I compared a lot of faces from Renaissance portraits in Photoshop. For instance, Albrecht Dürer (self-portrait at left) had a thing about hair:

Sometimes it’s not the faces that repeat, but a specific fixation of the artist. Other times, however, it’s not so simple.

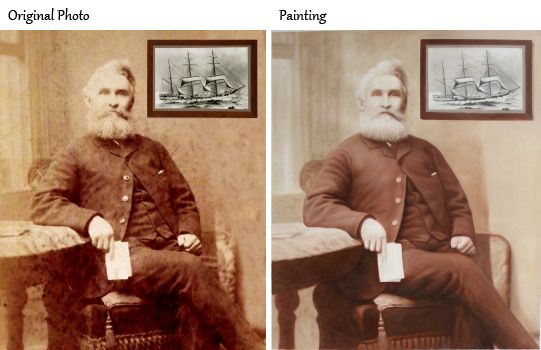

The painter’s own reflection in a mirror, after all, is the only thing that is available to them for free, whenever it’s needed. In short, perhaps automimesis is just a fancy name for a very practical solution. In those moments, quite understandably, painters tend to reach for a mirror. And all at once, the eyes you spent five hours perfecting look just a tiny bit off.

Even if they do, it’s inevitable that the light will change, or they will subtly shift their expression. If you’ve painted even one portrait, you soon learn that it’s really hard to get someone to sit still for long.

Portrait painter wanted professional#

I don’t paint much anymore, but for a time I wanted to be a professional artist, and I’ve spent thousands of hours in front of easels. One reason I find this topic interesting is because it gets at a fun but rarely noted aspect of historical research: experiential history, or knowledge gained from the real-world practice of the historical profession you’re studying ( here’s an example ). Below is a self-portrait by the Florentine painter Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510): They’ve uncovered a surprisingly complex history involving Aristotle’s theory of personality and Neo-Platonic philosophy ( here is a good article on the topic, and here ’s a new book on “the Involuntary Self-Portrait”).īut for now, a quick example so you can see what I mean. The tendency of painters to mirror themselves in their art was, da Vinci believed, one that revealed much not just about how the painter looked, but how they thought.Īrt historians have written about this idea, which they call automimesis, for well over a century. Leonardo da Vinci, for one, discussed it at length in his Treatise on Painting. It seems to have rapidly become a proverbial expression, capturing something of the ambient folk wisdom of Renaissance Italy. The earliest attributed source for the quote is Cosimo de Medici (1389-1464), the Florentine powerbroker and arts patron. Ogni pintore dipinge sé : “every painter paints themselves.” It was there that I first came across an idea dating back to the Renaissance.

Portrait painter wanted free#

When I was 12 or 13, I spent a lot of my free time reading art books at the library.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)